Trollkarlens hatt

After discovering a mystical top hat with magical properties, chaos ensues in Moominvalley as one strange event is followed by the next. Eventually two strange travelers appear carrying a suitcase with secret contents that are absolutely not to fall in the wrong hands.

The third book in the series, this sees the cast of the previous story Comet in Moominland returning for a more slice of life approach. Finn Family Moomintroll sees the introduction of the Groke along with the minor characters Thingumy and Bob.

With this book, Tove Jansson left the publishing company Söderströms and went over to Schildts, who would publish every subsequent book in the series. Incidentally, the two publishers would merge in 2012, forming the new Schildts Söderströms company.

This was the first story to be released internationally, being rebranded as a more definite starting point for readers. The original title Trollkarlens hat (The Magician’s Hat, referring to the character localized as “the Hobgoblin”) was changed to the overly informal Finn Family Moomintroll, which curiously put huge emphasis on the book’s country of origin. In the USA, the story was instead published under the title the Happy Moomins in 1951 (p. 166). For a significant amount of time this had the impression of being the first book in the series. As a direct result of this, several adaptations of the series treat this story as a framework for establishing a firm status quo, meaning otherwise insignificant characters like the Snork and the stamp-collecting Hemulen being given far more attention than they ever got in the actual books, along with characters like Sniff and Snorkmaiden who are eventually phased out in later books.

The characters Thingumy and Bob are clear stand-ins for author Tove Jansson and Vivica Bandler, reflected in their original Swedish names of Tofslan (Tove) and Vifslan (Vivica). Vivica Bandler was briefly Tove Jansson’s lover and subsequently a longtime friend. The two would go on the collaborate on several Moomin productions, including two stage-plays and a television series. The real-life connections have made Thingumy and Bob’s relationship with each other and the symbolic meaning of the king’s ruby that they hide and protect ripe for queer readings through a contemporary 1940s lens.

During the editorial process, two chapters of the book were cut out by the publisher to lower costs on printing (Westin & Svensson, 2014, p. 226). Two out of four unpublished illustrations survive depicting events from these chapters, one where the characters tidy the Moominhouse and drop a piano down a set of stairs, and a segment featuring the Hemulen’s Aunt, a character that was dropped and reused in the next book (Westin, 2007, p. 215, 216).

At a later date, Tove Jansson made smaller revisions to the illustrations of the book, presented below with the older version to the left and the newer to the right. The vignette of the transformed Moomintroll is completely redrawn, the map and silhouette of the Hattifattener’s Island has been modified to mainly appear less tropical and more Nordic. Primarily, most illustrations have minute detail changes with the most common being enlarged pupils, likely to fall more in line with the later finalized designs of the characters that had larger and more expressive eyes. The earlier illustrations have been sourced from English copies of the book as it’s never been updated since its initial translation, note that any text will be inaccurately presented in English because of this.

A series of unpublished illustrations depicts the cloud riding scene in greater detail. Likely for a cancelled revision of the book, judging by line work and character design this would’ve been somewhere around the 60s and falls in line with the reworked versions of Comet in Moominland and the Exploits of Moominpappa.

Initial pressings of the book used already existent illustrations for their covers, with the book only being given its first proper cover artwork with the 1956 Finnish translation. Two English cover artworks followed, one featuring a wreath motif with unclear dating, the other featuring a striking lineup of characters and events from the story in an aesthetic reminiscent of the first two picture books dated 1961 (Karlsson, 2014, p. 188). A final cover artwork was made in 1968 for a French translation (Honkasalo, 2017), featuring a wide depiction of Moominvalley, its inhabitants and events from the story. This artwork was also used for the 1968 Swedish reissue of the book as its new updated cover.

Complimentary decorative wreath added in some later issues of the book, presumably adapted from the cover with the same motif.

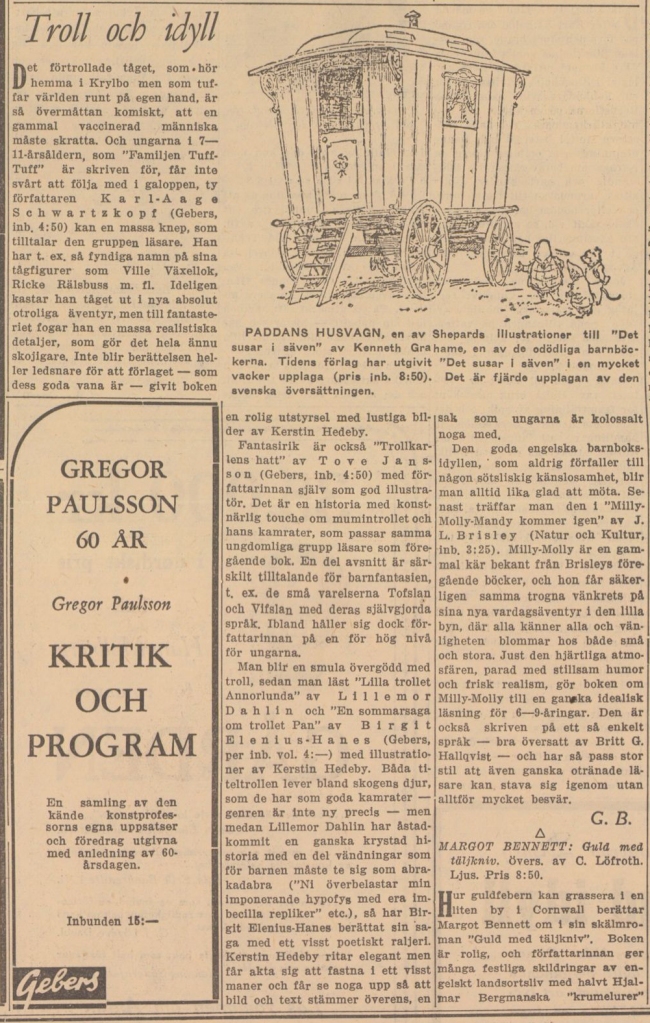

The book was the first to see slight coverage in Swedish press, with a few couple reviews giving it a slightly positive reception. Of note was famous Swedish children’s book author Lennart Hellsing giving the book a glowing review, noting influences from English literature in the writing and hinting talent and promise in the then upcoming writer.

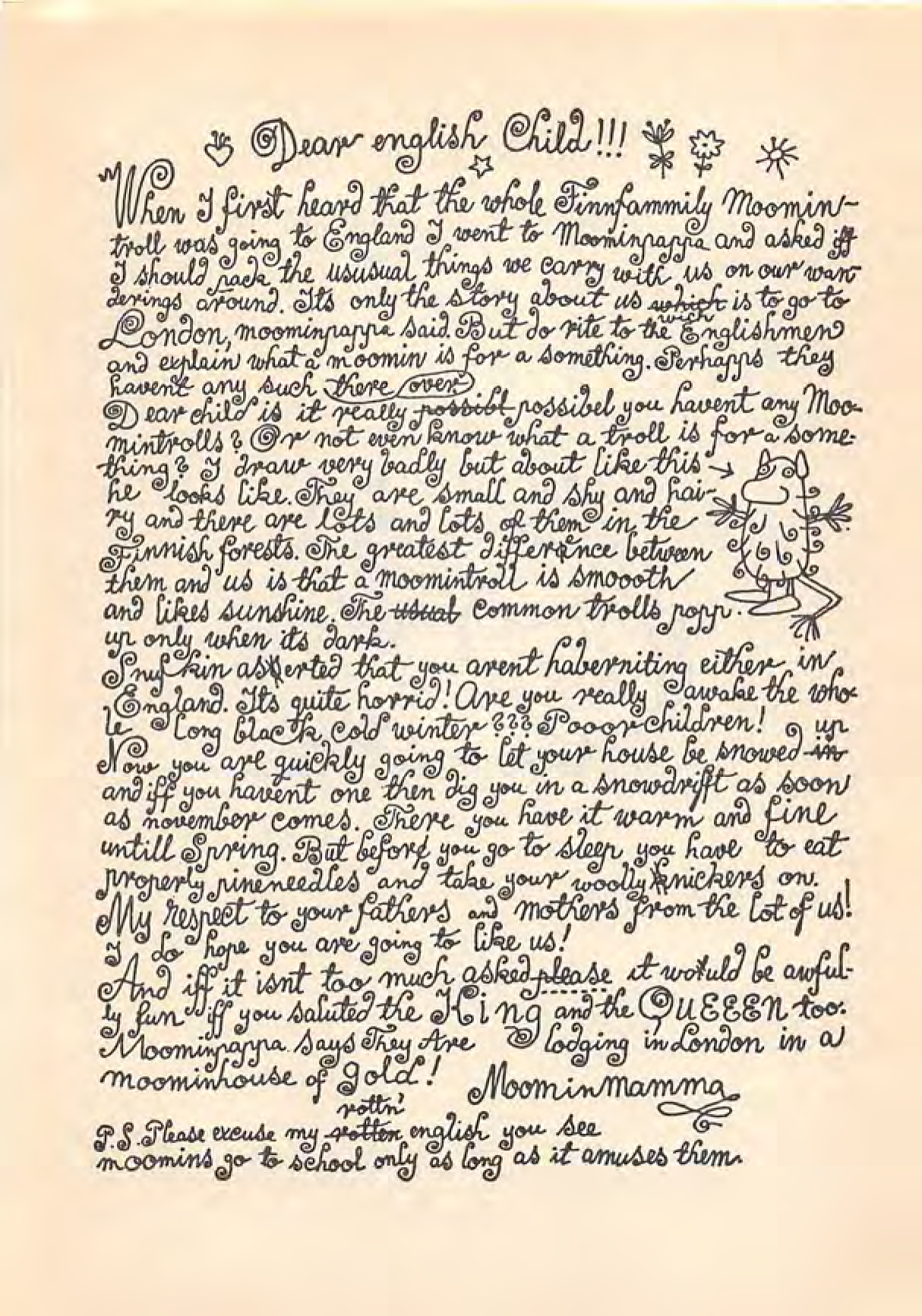

Early English publications added an extra page at the beginning of the story introducing the family in sloppy writing signed Moominmamma, this was in effect of the book being the first to be translated into English, with publishers wanting to provide a more proper introduction to the series than what was present in the original text. Likewise, early German publications supposedly added the detail of the family saying their prayers before hibernation. Tove Jansson did not approve of this change and it is believed to have inspired the line from Little My in Moominsummer Madness about not wanting to go to heaven (Karlsson, 2014, p. 111).

Early English publications added an extra page at the beginning of the story introducing the family in sloppy writing signed Moominmamma, this was in effect of the book being the first to be translated into English, with publishers wanting to provide a more proper introduction to the series than what was present in the original text. Likewise, early German publications supposedly added the detail of the family saying their prayers before hibernation. Tove Jansson did not approve of this change and it is believed to have inspired the line from Little My in Moominsummer Madness about not wanting to go to heaven (Karlsson, 2014, p. 111).

The localized names Thingumy and Bob for characters Tofslan and Vifslan went through a spelling change some way during the initial English translation, with the originally intended Thingamy becoming Thingumy. This has lead some people to misinterpret the name as a combination of “thin” and “gummy”, when the initial intention was for the two character names in combination to be pronounced like “thingamabob” (Westin & Svensson, 2014, p. 241).

Sources:

Honkasalo, M. (Ed.). (2017). Guess What Happens Next? Tampere Art Museum.

Karlsson, P. (2014). Muminvärlden & verkligheten: Tove Janssons liv i bilder. Bokförlaget Max Ström.

Westin, B., & Svensson, H. (2014). Brev från Tove Jansson. Schildts & Söderström.

| Published: | 1948 |

| English translation: | 1950 |

| Finnish translation: | 1956 |